CO2 Sequestration In Methane Hydrates

Table of Contents

Extracting Fire From Ice

In 2011 and 2012, I was part of a team that developed, deployed, and supported a data acquisition and analysis system for Schlumberger and ConocoPhillips in Kuparuk, Alaska. This remains one of my favorite field support trip experiences to tell.

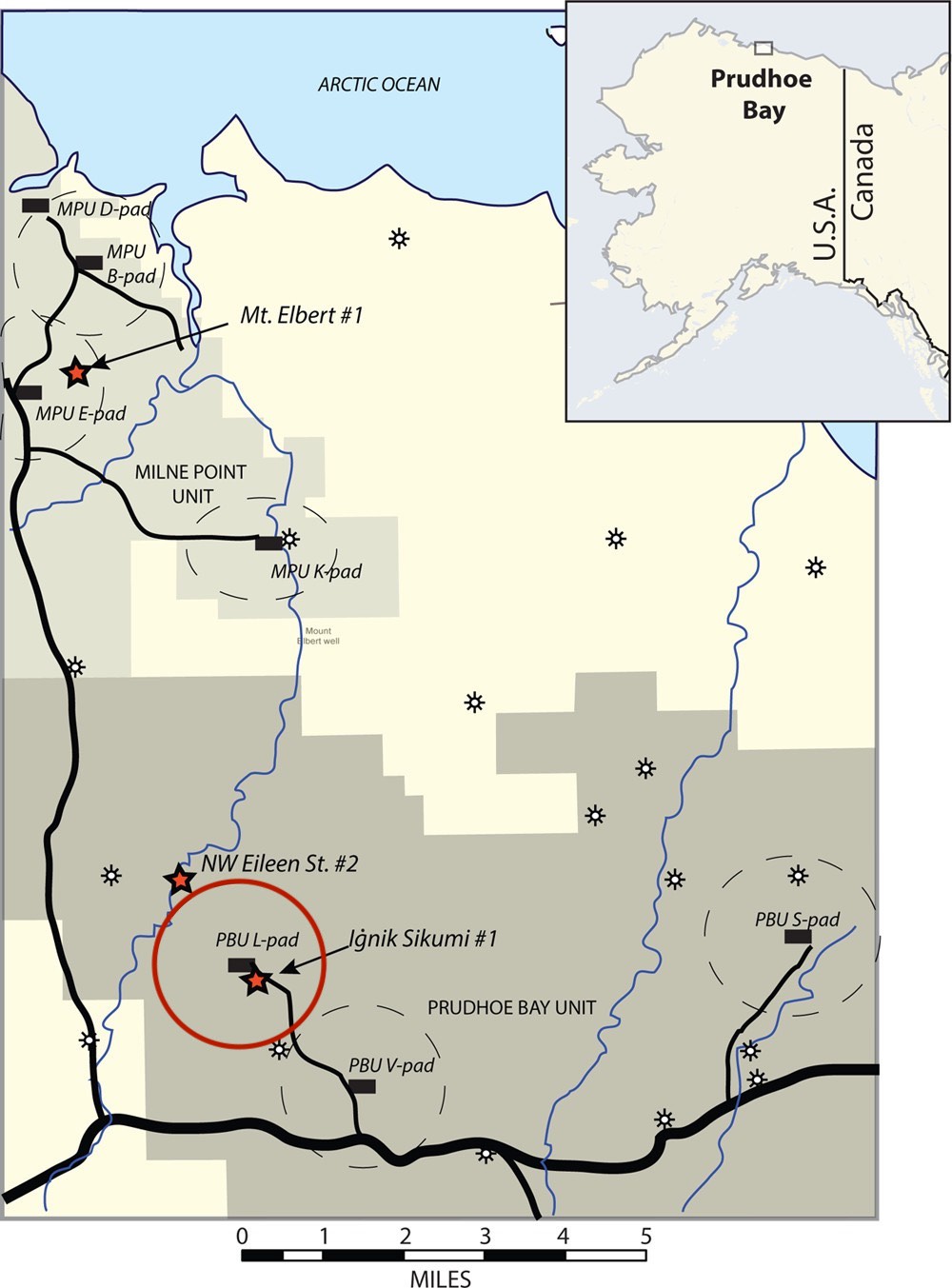

Ignik Sikumi #1 location. Image: Modified from ACS Publications

ConocoPhillips had been working with the DoE on a feasibility project to determine if there was a way that carbon dioxide might be able to be stored away (sequestered) during the fracking process. The theory was that during extraction of the gas, one might be able to pump CO2 back into the bore hole to:

- Increase the stability of the gaseous formation by replacing the natural gas in a volume-for-volume basis and

- Maybe re-trap some of that pesky atmospheric CO2.

A project was formed and named Ignik Sikumi, an Inuit phrase roughly translating as “fire in the ice.” The scope of this project was to determine if natural gas that is trapped in sand, mixed in water, or other combinations of materals (“hydrates”), could be successfully extracted while simultanously using carbon dioxide as a means to decrease atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations and to ensure pressure is maintained down well.

We were contracted to help design the system that was responsible for data acquisition and regulation of gases. The design was done predominately in Texas while the final deployed system was in Kuparuk.

In order to make this all feasible and straightforward to get from Texas to Alaska, we had to design and build everything to be portable and conform to shipping standards. Our mechanical team literally transformed a standard size cargo shipping container into a portable laboratory; it was something else.

Two doors were cut into the sides of the container and it was split into two sections. About 15% of the container was dedicated to the area for operators and engineers. In Texas, 3-4 people could fit comfortably in here. In Alaska: just two. The fabrication team even built in a window here! This turned out to be a great thing (ominous foreshadowing).

Turns out arctic PPE is pretty bulky. This image of me has been featured in a health and safety briefing for I think every company I’ve work for to date. Image: Nick Aroneseno

The other 85% of the container had all the VFDs, flow meters, electrical cabinets, a gas chromatograph, DAQs (we used NI cRIOs and Allen-Bradley PLCs in this case), and manual controls. This was separated from the control area by a partition with a window so you could monitor the equipment.

A view into the equipment chamber of the skid during checkout in Texas.

DAQ

In order for this project to be successful, the powers that be needed all the data from the flow meters, gas injection VFDs, and various other sensors to be logged and simulcast to the home base (not in Alaska; I think maybe Europe). We designed the HMI around LabVIEW to ease integration with the real time code on the cRIOs and used it to log all data to a local database (MySQL, if memory serves). This was then copied to a secodary PC for data safety purposes. This secondary database was then read by another PC in the main habitat, separate from the control shipping container, on a LAN we had setup for the researchers to parse in relative comfort; a satellite link was also used to copy this data to HQ.

Who Are You?

After dry running and dress rehearsal in Texas, we shipped the container in December to the field site in Alaska. I met it for my first rotation towards the middle of January. I remember this distinctly, because for the first week or so we had no communication with the outside world except via radio relay to base (they finally got the satellite linkup working the morning of the Super Bowl that year to make sure people could watch the game on a rare break. Priorities.).

I flew in from Anchorage on a 737 charter to Deadhorse, Alaska (I’d love to know the history of that name). This ‘airport’ (a stretch of ice scraped of snow) is like most things on the North Slope, a raised building from the ice with minimal creature comforts. It was probably no more than 50x80ft. The baggage handlers were divided by a simple curtain. Yes, there was still TSA.

I was told before I left that a representative from the client would be waiting for me. I saw no one, and after asking around with still no progress, I waited. There is no cell service up here. I waited for about two hours until TSA wanted to close the airport for the day and told me to shove off. Explaining that I had no idea where to go and literally have no means of communication with anyone, they finally radioed in to god-knows-where and another half hour later was greeted by my handler.

Habilitation units on the move.

Mind The Bears

It’s a 45 minute drive from Prudhoe Bay/Deadhorse to Kuparuk where we had our pad location, but my handler wasn’t ready to leave yet. I ended up mulling around in the main ConocoPhillips building until he was ready to depart. I completed my safety orientation (if you see a polar bear, GO BACK TO THE REBAR ‘AIRLOCK’ CAGE IMMEDIATELY), enjoyed the cafeteria (side note: even on the pad location, they made sure to feed us well. There were two dedicated chefs for 24/7 coverage and I don’t think I’ve eaten better since. Fresh cookies every 12 hours, steak a few times a week… I mean, what else are you going to do on your down time), and was able to find a spot of WiFi (not ubiquitous back then) to check in with my team and grab the latest schematic updates and software patches.

There is an airlock-esque two stage entry system for most of the remote pad sites. The idea is that if you see a bear, you can quickly get into a cage and be somewhat more safe than just being on the frozen tundra. Our location didn’t have this!

Storm

When finally ready to depart, we unplugged the truck (for those not accustomed to extreme cold weather climes, the vehicles need engine block heaters that you must plug in when not actively using the vehicle, lest they freeze up. If they do, it’s not moving until it thaws out in late Spring) and made our way up North to the pad site.

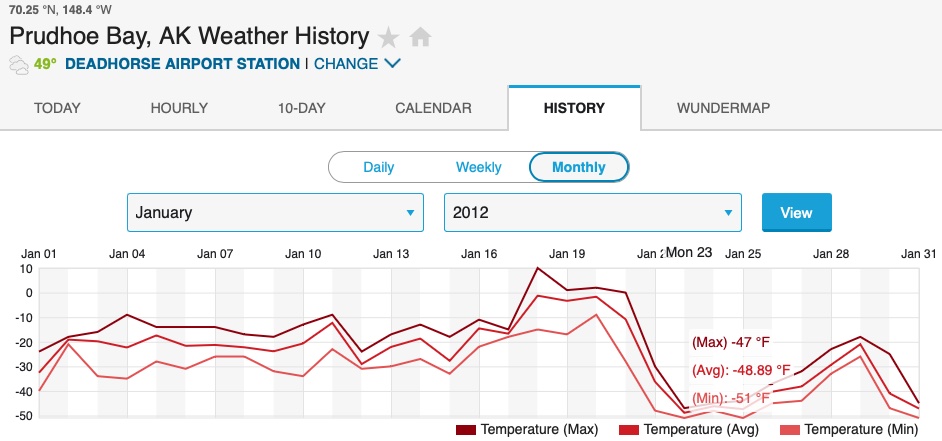

I arrived for my first rotation literally just in time. The temperature was already plummeting during the 40 mile ice-road drive from Deadhorse Station to Kuparuk to the final pad site. That night, the local temperature fell to -70°F. Without wind chill. Literal icicles formed near my head in my bunk. We had a few storms during my month stint, but none as bad as that first one.

The closest I could find was Deadhorse Airport.

Remember that LAN we set up? This was done using fiber optic running ~1000ft from the main habitat (also built out of shipping containers) to the control container. The first storm was so cold that it caused the fiber optic strands to shatter. It was not pleasant for the team that had to re-trench another link in that weather. My eternal sympathies, fellas…

In order to keep the equipment from freezing up, a mobile heater was pumped in through that window in the control section of the skid.

Data

Our LabVIEW application performed pretty nominally overall. There was one exception during the first part of the trip where it would be nice and snappy and would then bog down and become sluggish. This was ultimately traced back to a memory leak where the database references and data weren’t being properly cleared (close your references folks!) since new ones were made at each call during the transfer step to the backup PC. When that was fixed, it was a whack-a-mole game of engineering. We had equipment failures (getting a part expedited out was always fun - “you want this shipped where?) (usually from the cold), ongoing development efforts as the researchers routinely wanted new features or data to be displayed in various ways, and general gremlin hunting. We got there in the end.

While limited conclusions could be drawn on site, we could at least verify that we were successfully injecting CO2 into the well. In fact, I think it was early on that they realized that mixing CO2 and nitrogen as a carrier performed significantly better.

Who Are You (reprise)?

My support was split into two 24/7 two week trips. I don’t really have much more to add other than when I arrived for my second stint in Deadhorse, I was forgotten about again. I’m still salty about it.

Fun Times

In all, this is by far and away one of the most demanding on site projects I’ve ever had to do. Between the weather, the long hours (I think 105 hours of active work still remains my longest single-week timesheet to date), the location (only having a low bandwidth satellite link that can barely relay voice) and isolation, this is definitely a story I pull out on a routine basis for interns or new hires (I’m getting into “back in my day” territory, and I’m not ashamed of it).

It’s been really neat to have a retrospective on this project all these years later, especially now that there are a number of long term data studies to read. The researchers were able to determine that it would be feasible to store CO2 down well provided that it is kept above the freezing temperature of water and that it’s mixed with N2 as a stabalizer and carrier gas.

References

- https://netl.doe.gov/node/6324

- https://www.usgs.gov/centers/central-energy-resources-science-center/science/successful-test-gas-hydrate-production-test

- https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1214906

- https://www.energy.gov/fecm/methane-hydrate-field-studies

- https://www.usgs.gov/publications/ignik-sikumi-field-experiment-alaska-north-slope-design-operations-and-implications

- https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/business/2012/11/11/alaska-ice-energy-source/1697387/

- https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.energyfuels.6b01909